Interview with Simon Šerc, a versatile cult creator in the field of experimental music in our country, the founder of the groups PureH, Cadlag, the Biodukt project, and the driving force behind the internationally recognized label Pharmafabrik. A noise artist who resonates louder abroad than at home.

by Žiga Jenko / Centralala

Was music important to you during your childhood? What did you listen to? Are your parents musicians or music lovers? Did the music they listened to influence you?

Music was always present at home in some way. My father played the drums, and he had a collection of records from the 60s and early 70s, which I enjoyed listening to as a child: The Animals, Rolling Stones, Status Quo, Hendrix Experience, Bee Gees, Beatles… primarily rock and pop, but also classical music, from Richard Wagner to jazz. He even had the first Yugoslav jazz record, the Ljubljana Jazz Ensemble. Quite a wide range of music, those were my first musical influences. Additionally, due to my father’s work, I often visited hydroelectric power plants on the Soča River with him, and from a young age, I was fascinated by the noisy sounds of turbines and the humming of electrical transformers.

Where did your enthusiasm for music come from?

As I mentioned before, initially it came from my father and his vinyl records, as well as my sister’s. Later, various influences from TV, from Dario Diviacchi to MTV, came into play. By the end of elementary school, I was already listening to metal. I loved exploring and searching for new sounds. Among others, I was inspired by Igor Vidmar with his show “Drugi val,” which I followed regularly in the late ’80s. I recorded the shows on cassette tapes and first heard bands like Head of David, Amebix, Killing Joke, Unseen Terror, Skullflower, Napalm Death, and albums like “Scum” and “From Enslavement to Obliteration.” Later, I made contact with the collaborators of the show. Doblekar recorded new releases from the metal scene for me, Gorenc from Rock Vibe sent me cassettes with more experimental bands, Boco and Galičič supplied me with various noise-grind projects… and many other friends, Miha, Hruki, Štrosar, Repše… This was a culture of endlessly copying audio cassettes, and I had a cabinet full of them, which I still keep. A significant influence on me was also the release of “Symphonies of the Planets” (NASA Voyager Recordings) – I think it was around 1992 – when I heard these recordings, I was completely euphoric and dove into creating ambient music.

What was the music scene like in the Vipava Valley back then? Were you just a concert-goer, or were you active in organizing concerts, working in a club, or being in a band?

I didn’t organize concerts myself, but Gorazd Repše and Sašo Kotnik brought many alternative bands to the Vipava Valley. However, that music scene wasn’t exactly to my taste; I missed more industrial, grind, metal, and alternative electronic music. For more interesting concerts, like Godflesh, I had to go to Italy. I hung out with metalheads from Ajdovščina, and we listened to bands like Sodom, Venom, and Bathory. Soon, I switched to more industrial sounds: Godflesh, Sonic Violence, Treponem Pal, Skin Chamber… I was active in various bands and quickly connected with like-minded extreme music enthusiasts from Nova Gorica. Later, I moved to Ljubljana, initially going home on weekends, but eventually, I stopped doing even that, gradually losing touch with the scene in the Vipava Valley and the Goriška region.

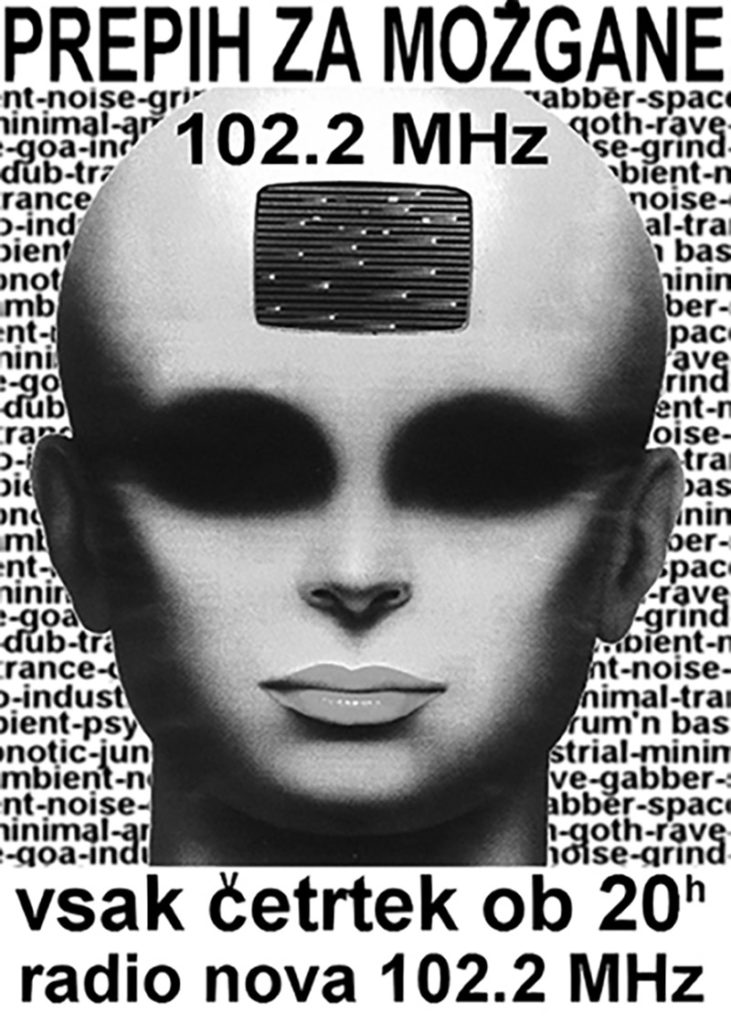

I should also mention the radio show I had on Ajdovščina’s Radio Nova in the ’90s, featuring new releases in alternative and experimental electronics. Various labels sent me promo albums by mail, and I especially owe thanks to Big Cat Records for sending a lot of material. There was no shortage of new music: Experimental Audio Research, The Orb, Autechre, Scorn, Techno Animal, Paul Schutze, Meat Beat Manifesto, Aphex Twin, FSOL, Aube, Merzbow, Panasonic, Coil, and similar artists, along with some older ones like Stockhausen, Riley, Subotnick, Charlemagne Palestine… However, there were some criticisms from the radio owners and especially listeners about the selection of overly radical music, as it was also being played in all the pubs and bars that had the radio on.

What was your first instrument? What drew you to playing it?

I can say that my first instrument was a computer, the Commodore 64. In elementary school in the ’80s, I experimented (or rather, played around) with the sound generator in the C64, the demo scene, and even bought a book on assembly language and did some programming. These were my first steps into electronics and computer noise. I modified the computer a bit with an audio input, it crackled, and I even burned out a SID chip once, but it sounded great to me. From those times, I have some demo tapes with various 8-bit lo-fi sounds/tracks. Among “real” instruments, I started with the bass guitar. At first, I had a semi-acoustic one, but I soon replaced it with an electric one. I’ve always been attracted to the lower frequencies of the bass guitar, and this influence is evident in all my projects, where the bass occupies a prominent role in the mix, whether it’s illbient, drum and bass, or drone and ambient. Equipment wasn’t as accessible as it is today. For anything more, I had to go to Godena in Stara Gorica. Effects were expensive, so I made my first distortion out of a broken car radio. I also soldered together a 4-channel mixer; basically, the equipment was more DIY, homemade.

Was Extreme Smoke 57 your first band that you played in? Which other bands have you played with?

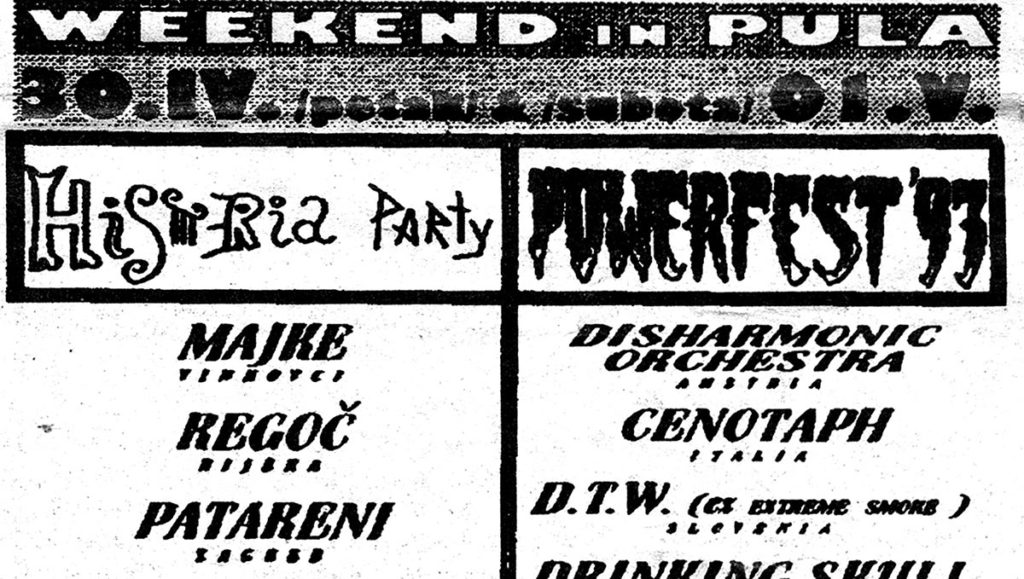

With Extreme Smoke, I was only involved in one album. In 1994, at Borut Činč’s studio, we recorded “Who Sold the Scene?” – the drummer was Cubase, Štrosar and I recorded guitar and bass respectively, and then we added various samples of engines, grinders, and Boco’s crackling. Over the course of nearly three decades, the album has become somewhat cultish, even described as “one of the most timeless grindcore albums of all time.” By the way, a decade ago, on the 20th anniversary of the album, we recorded a sequel, “Who Sold the Scene #2”. Before that, I played bass in the band Deeper Than World (DTW), and with Boco and Tom, we had a d-beat/grind band called Earslaughter, where I played guitar, along with other projects. For a while, in 1992/93, I was also a member of the Zagreb noise-core group Patareni. Before that, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, I was in various garage bands. As for the Patareni – Hadžo, the founder of Patareni, was looking for a rhythm section for the band, a bassist and a drummer. I said, “Why not?” and activated a drummer, and we took the train to rehearsals in Zagreb. There, over one weekend, we rehearsed a bunch of songs, made some new ones, and then went on tour.

Did you perform a lot of concerts, and how different was the scene back then?

With DTW, we performed in various clubs and festivals, alongside bands like Fleshcrawl, Disharmonic Orchestra, Pungent Stench, and Cenotaph; with Patareni, we went on tour in Germany, to Leipzig, Husum, Freiburg… it was quite eventful. The scene was more homogeneous back then, more specifically defined and oriented towards certain genres. The accessibility of music was limited to physical formats like tapes and records. Today, genres intertwine, there are countless factions and hybrids, and music has moved to digital platforms, which have changed the way it is promoted and listened to. Back then, listeners and musicians weren’t as diverse in their musical preferences; now they are much more receptive to different genres and forms. What was underground grindcore then, is now something like noise. We made drone music when we forgot to turn off the amplifier; today, it’s a whole genre. Hyperproduction has also become very pronounced due to technological advances, which allow easier access to recording and distributing music.

Did you leave those bands to create the PureH project?

In parallel with those grind-noise-core projects, I also worked with computers and electronic sounds. Things were happening in electronics at that time: new machines, new software, new sounds, new genres… I started experimenting more and more with electronics. As mentioned before, initially with the C64, later in high school, I swapped the Commodore for a PC and acquired various sound cards, effects, and samplers. I studied computer science, so programming and various SCSI, MIDI connections were not unfamiliar to me. I discovered a new world because I could sample my own sounds, process them beyond recognition, and then play those samples with keyboards, implementing them into compositions. There was a lot of experimentation, but above all, a lot of work. This was before various automations in sequencers, and there were no loop/slice tools like ReCycle, for example, which later made the work much easier. RAM was always scarce, disks were small, so we had to save to slow tape drives. Software effects were more offline than real-time.

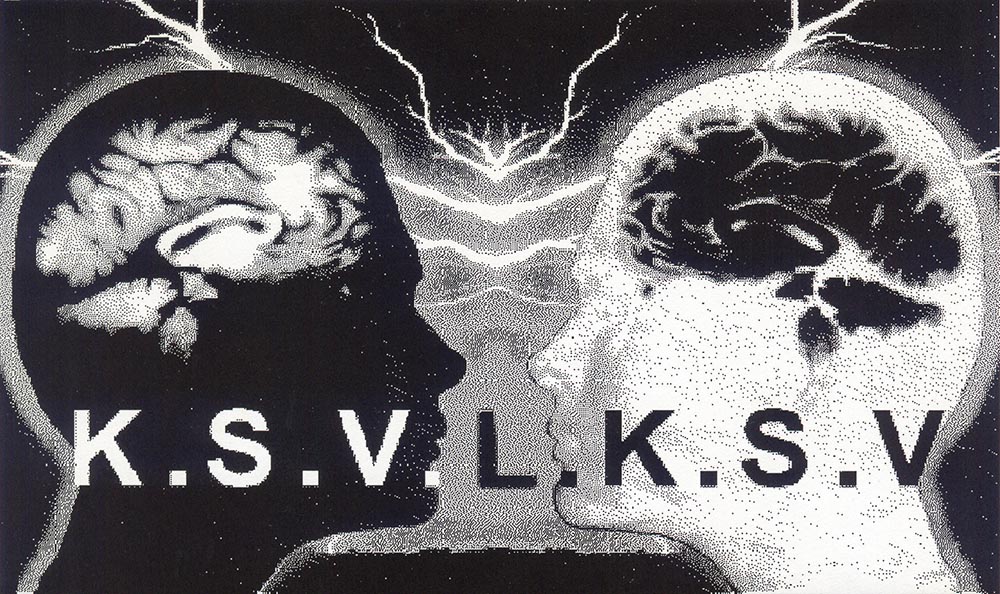

Before PureH, in the early ’90s, I had other electronic projects, such as the hypnotic ambient Inertia, then the atmospheric industrial ngc6559, the psychotic Spheres, as well as Am I Human?, Puredope, harsh-noise illbient KSVLKSV, etc. Matjaž Galičič, the organizer of Noisefest, described KSVLKSV as one of the first Slovenian electro-noise projects in a review of the Slovenian noise scene.

Break21 – K4, 1997 (Delo).

What was the initial idea behind the PureH project? It started as a band. Who was involved in PureH?

It started as a one-man band. PureH was basically just one of many projects for me – I had a different name for each genre. At the beginning, it was more ambient/breakbeat and drum’n’bass – a fairly new style at the time, promising. I performed alone or invited someone to join me; it looked more like a performance. I had a two-meter iron robot flashing under the stage, with video projections in the background. In Maribor in 1997, I performed with a laptop for the first time; at that time, having a computer on stage was quite a novelty. For a concert at Novi Rock in Križanke, I invited Vili Žigon (the drummer from DTW mentioned earlier), who replaced programmed rhythms with real drums. This made the music even more layered and complex, emphasizing its aggressiveness and dynamics, and the performances became visually more interesting. Later, Jernej Kolenik joined on guitar, and then Sergej on bass. So, PureH was one of the few Slovenian bands that simultaneously embraced electronics and direct guitar approaches, as well as acoustic drums. There were various DJs on the scene spinning drum’n’bass, breakbeat, techno, but we played it live with real drums and bass, with a guitar, which made us interesting to a wider audience, not just club-goers. We were invited to festivals where we played on bigger stages alongside bands like Demolition Group, Psycho-Path, Laibach, Big Foot Mama, Shyam, and Oko, at festivals like Novi Rock, Off Rock, Art&Music, Lent, Expo, Break21, and Šourock, among others. We also received some awards, like the Maršev Gojzar award and the Studio City Bumerang award. For example, in the info material at Expo in Hanover, we were described as “a band that started a new musical revolution in Slovenia.” From the beginning, I incorporated video projections into our concerts, mostly computer animations and digitally processed VHS recordings, displaying a mixture of shocking and morbid images, all synchronized with the music. Various vocal samples from movies were also displayed on the screen simultaneously. We played in darkness, illuminated only by the projector, so the video was highlighted as much as possible, and the whole concert felt more like a film with a live soundtrack – this similarity can be seen in my current live project, Cadlag.

How has PureH evolved to this day? If I understand correctly, PureH has also become your artistic name under which you have solo performances with ambient experimental music?

It would be nonsensical to pigeonhole PureH into a single genre. Counting all the other factions, the sound has changed from ambient, noise, and psychedelia in the early 90s, then to breakbeat, dub, and an illbient-industrial phase with slow rhythms, later into some kind of exotic ambient-core and eclectic drum’n’bass with dark undertones, which, albeit radically interpreted, approached more guitar-based, industrial music. Mostly, I recorded everything myself in my studio. The mix and mastering for the “Chinacat” EP were done at Alien Aldo Ivančič’s studio. One mini-album was recorded at Peter Penko’s studio from the band Coptic Rain, but it was never released. After 2000, I started engaging in other projects, with video and programming, and PureH fell silent for a few years. The “Anadonia” album was again a darker illbient with elements of krautrock and a homage to the Spheres project from 1995 with three drummers, alongside Vili, Boštjan, and Denis Kumar, which was then remixed by KK Null, Eraldo Bernocchi, DJ Surgeon, P.C.M., Chris Wood, and the rest of the team.

I wouldn’t say that PureH is my artistic name; it’s just one of the projects/names. A few years ago, I performed in Velenje with the PureH project, but I performed under the name KSVLKSV. In Maribor at Kiblix, I performed with material from CMBR under the name PureH… it’s all a bit confusing with the names. The current mood is more ambient-drone-experimental; I find it easier to perform this alone live. Even when we were still a band, there were many ambient inserts between rhythmic pieces. However, I’m in touch with Dejan and Vili, and perhaps in the future, PureH will be a live band again with acoustic drums and bass, which we’ve been discussing for, hmm, 20 years…

You’re also involved in the group Cadlag, which consists of several recognizable musicians. How did you come together, and when did the collaboration evolve into a band?

Cadlag is another project of the Pharmafabrik label. I released my first two albums with Neven, and we often talked about doing a project together. This happened in 2012 when I arranged Alexei Borisov’s performance at Noisefest in Ljubljana. Galičič told me that some bands had canceled their performance and asked if I could step in with one of my projects. So, the project Ontervjabbit was created for Noisefest, in which I was also involved for some time, and we released the album “Derivat.” Concurrently, the Cadlag project also emerged, focusing more on drone-oriented textures rather than noise. I invited Dejan Brilj from Ajdovščina to collaborate, and Boris Laharnar, a guitarist from Trbovlje, joined us – we became a quartet. After our first performance in Italy, we soon went on a short tour to Austria and the Czech Republic. Rather than focusing on club performances, we prefer unconventional venues, from claustrophobic mines to noisy performances in gothic cathedrals like Votivkirche. There’s also a Cadlag spin-off project called Myrornas Krig, improvisational ambient-noise with dancers on stage. We performed for Ne(formo) and at the perAspera dance festival in Italy.

Does the music stem from a particular concept?

We come from different backgrounds, and various genre patterns and influences of experimental electronic, grindcore, noise, ambient, drone, and cinematic, perhaps occasionally classical music, can be felt. As for the concept: Cadlag’s performance is an auditory journey with dynamic peaks and troughs, sometimes brutal and paranoid, other times elegant and moving, with sound layering ranging from minimal ambient landscapes to the most extreme outbursts. The recognizable sound of Cadlag is contrabass drone, layered with reverberated and modulated guitars, glitches, hisses, and of course monochromatic visuals.

A very important element of Cadlag’s performance is also visualization. How significant is it for the music? How much does it influence the concertgoer’s experience alongside the sound?

I had quite a bit of still functional analog video equipment from the 90s, some even from the 80s, like VCRs, cameras, which are all practically useless for modern production. So, I came up with the idea of using analog video projection in the opposite direction alongside analog instruments for the Cadlag project. Massive sound structures are visually complemented with television noise and VHS textures of demagnetized videotapes. A large screen is placed between the stage and the audience, onto which this video noise is projected from the background, capturing the shadows/silhouettes of the performers. For the observer, it all resembles a film projection, where the musicians are actors, creating a kind of real-time audiovisual installation, infused with cosmic delirium from all sides of the frequency spectrum.

Does Cadlag’s concert performance differ from the process of recording albums?

With Cadlag, it’s all about pure improvisation, unpredictability, the intensity of the performance; every concert is different. We don’t have any rehearsals; we meet at the concert, define, for example, the dramaturgical concept, perform, and simultaneously record. The album usually consists of these live recordings – in the studio, I listen back to them, master them, and then transfer them to tape. I choose the album concept and title, put together the video, and package it onto some obscure analog medium, like a VHS tape or a 5″ reel for collectors.

Lately, you’ve also been releasing music under your own name. It seems that it involves field recordings that you process in one way or another. How does the creative process differ or remain the same compared to PureH?

Field recording differs quite a bit from studio recording, where you have everything under control. In the field, you’re exposed to various noises and random sounds, recording in different locations, maybe “in-situ,” waiting for something to happen, or as a “drop-rig,” where you capture the most authentic nature recordings in the absence of human presence. I do a lot of hiking with Martina Testen, and the obligatory equipment in our backpacks always includes a recorder and a microphone. In the end, you accumulate tens of hours of recordings, which need to be listened to, cataloged, cleaned up, selected, and organized in the studio to create a coherent, logically connected narrative. Some recordings are sculpted or collaged, while others retain their documentary value in their unmodified form.

Under my own name, I also released the CMBR sonification album, where the creation process is essentially programming; everything was composed algorithmically. I took a huge dataset, the Planck mission data, as input; the output was hundreds of rendered sounds and numerous hours of abstract “music” created by algorithms – from pure noise to pleasant ambient patterns. Everything was then selected and further processed; I used various sounds during live events, processed live. The project was first presented at the Sound Thought festival in Glasgow in 2017, then at various festivals in Korea, Serbia, Greece… Later, I selected four compositions for release with the Silent Records label. Since the first public release of the Planck mission, I knew I had to translate it into an audio signal. Since the input data is taken from the oldest detected signal, the album’s sound could also be called the ultimate noise of the universe.

How does your album creation process unfold? What determines the equipment you use, and what do you use for music production?

It depends on the project – for projects like Cadlag, I use only the double bass, effects, or mini analog synths, sometimes an AM radio for noise. For other projects, I use everything at my disposal, from software like MAX/MSP to hardware, various acoustic instruments: bass, double bass, guitar, electric violin, various synths, effects, controllers, gadgets, even a collection of ethnic instruments from didgeridoos to thumb pianos and Slovenian clay whistles, frogs, rasps, and the like, all of which I process with effects to create a new sound. It all starts with sound, on which I build, transform, and search for subtle variations and textures. Generally, I don’t use external samples or sounds, except for vocal monologues taken from older cult films. In the early nineties, I mostly used just guitar, bass, sampler, effects, and a computer; in the 30 years since, I’ve significantly increased my arsenal – the essence and most important thing are that I have everything within reach and interconnected, so I can record something immediately in a moment of inspiration and not waste time setting up and connecting cables.

Do you record spontaneously all at once or in layers? What does it take for you to decide to release an album?

Both, I either improvise everything at once or record in layers for more complex structures; this process hasn’t changed much for me fundamentally in the past 30 years. Mostly, I just record and don’t release – I have material and fragments for quite a few albums on disks, as well as a large library of field recording sounds, from almost inaudible insects to noisy industrial sirens. I usually decide what to release several years after the recordings are made – when I hear the original compositions with “fresh ears.” Often, I forget about recordings; they get lost in various folders and backup disks, or I make multiple versions of the same song or album and can’t decide which version is right. Over the years, and especially with work for other clients, when you have a deadline, you tend to procrastinate less. It’s good to set deadlines for yourself. Albums are rare also because I don’t like all the logistics that come with releasing – printing, distribution, promotion. If you release an album today, you have to promote it at least a little; otherwise, it’s pointless because no one will hear it in the flood of production.

The same goes for albums of field recordings – nothing was planned; I recorded the storm for myself because I wanted to capture a moment of extreme weather. It was only years later that I decided to release it; such extreme storms, 200 km/h, are no longer common in Ajdovščina; it’s often windier in Nova Gorica. Biodukt was created for Martina’s research, several years before its release on an album for a wider audience, as an experiment conducted in a supermarket where the radio program was replaced with sounds from nature, and it was observed how much longer people lingered in the store. It was released at the right time, during the outbreak of the coronavirus and the general lockdown.

You also perform at festivals abroad, such as Sound Thought (Scotland), Gravity Assist (U.S.A.), Black & White (Portugal), Lieblichkeit und Sexualität (Austria), Art & Music (Croatia), Expo 2000 (Germany), Instants Vidéo Numériques et Poétiques (France), Sguardi Sonori (Italy). How do you get these opportunities to perform abroad?

It varies, mostly through email and contacts; there are more opportunities and various festivals abroad than in Slovenia. David Rastas from Kunstglaube invited us to the Lieblichkeit und Sexualität festival; Jani Novak from Laibach called me for Expo2000. For Art & Music, I had a link through the now late Sandi Maver, and at the Sound Thought festival, I premiered the CMBR project… Over the years, I’ve built a network of connections, friends, acquaintances; I usually get invitations via email, and I also receive numerous messages daily for various open calls, which I haven’t been opening lately; there are too many. However, I don’t perform a lot; it’s more of an exception than the rule; I prefer studio work.

Your music is also covered by media at home and abroad. How important is media presence for a musician? How have the media changed since the beginning of your musical career?

Media presence generally helps with recognition and gaining new audiences, providing better access to sales channels; even an article or mention in well-known media outlets like The Guardian, BBC, or The Wire immediately reflects in increased sales. Maybe because of this article/interview, someone will hear about me for the first time or even buy an album. At the beginning of my career, we focused on traditional media – radio stations, TV, newspapers, and fanzines; with the rise of the internet and the emergence of digital media platforms, new opportunities for discovering and promoting music have emerged. We all experience this as euphoria in the form of promotion, digital sales, file exchange, while also suffering from all the pathology of this system.

You also run the Pharmafabrik label, which has been around since 1993. Why did you decide to start a label? What is the concept of the label?

Initially, it was just the name of the bedroom studio at the time; the label in its current form began to take shape later for cassette releases, for my own projects. Then, with CDs, it became almost a necessity; you needed a registered label and a bunch of paperwork for the factory to replicate your CDs. As for the concept: every label seeks its own image and name, and Pharmafabrik was a logical choice for a label that produces an escape from reality. Maybe I was looking for radical difference, and perhaps the best way to show this is by creating different music – something that doesn’t produce the indifference served to us by the media, which constantly bombard us with the museum of art and commercial materialism. A music critic wrote some time ago that the Pharmafabrik label significantly enriches the audio diversity of the local scene with its activities, promoting innovative and progressive electronic music. So, that’s probably part of the mission too. The feedback from customers is positive; the alternative electronic scene in Slovenia is much more developed today than it was thirty years ago. Some musicians have told me that because of the PureH project in the nineties, they started producing electronic music; the label’s releases have influenced many to start listening to and creating this type of music.

You also release music by other musicians through the label; what is the selection criterion?

Later, I started releasing albums by other bands/projects and Fabriksampler compilations, kind of “encyclopedias” of all kinds of factions and hybrids, from ambient, minimal, noise, dark ambient, illbient, drone, psychedelia, etc. The tracks for these compilations are made exclusively; I invited well-known and lesser-known musicians to participate, such as Justin Broadrick (Godflesh, Techno Animal), Mick Harris (Scorn, Lull), KK Null (Zeni Geva), Mike Browning (Morbid Angel, Nocturnus), Sunao Inami, Nordvargr, etc. In essence, these compilations and excellent reviews in foreign media somewhat contributed to the label’s greater recognition. For the compilations, I know exactly who I will choose and contact them; for the albums, it varies, more spontaneously – Browning contacted me, saying he had recordings that might interest me; I had been in contact with the musician Go Tsushima and the Psychedelic Desert band for a while, and I released their first album; I met Daniela Buess at a joint concert with Mir, and he sent me recordings; I’ve known Luka Prinčič since the 90s; I found Neven Agalma on Myspace and released his first album, etc. For many years now, I’ve been receiving various demo and promo recordings every day via email, asking if I would release them on Pharmafabrik. Once a month, I take the time to listen, and if something interests me, I contact them. The selection criterion is simple: the music must attract me.

You release small editions of albums on physical formats like cassettes, CDs, video tapes. Do you think this makes sense given the increasing digital consumption of music through various platforms? Why? Is it worth it?

It makes sense, let’s say, but it’s definitely not profitable. It’s more about enthusiasm. In the past, editions were larger, but lately, everything is mostly limited edition. There are still people who enjoy buying physical media; even some reviewers prefer physical releases over digital ones. Collectors seek rare and limited editions of albums; for example, there’s an interest in releases on reel-to-reel tapes, which were popular in the 60s and 70s, mainly due to the specific sound characteristics; enthusiasts are willing to pay more for these specimens. Generally, though, small editions are not financially sustainable; digital sales cover the loss. Today, Pharmafabrik is a boutique label; a few releases per year are a constant, as well as intervals where nothing is released for several years. Essentially, it’s still a one-person project doing things that have long lost their significance, except in an advertising sense. Progress continues, and production accelerates itself as much as it becomes indifferent to its original purpose.

The second-to-last release from the label is the compilation “Bora Scura Reimagined.” The common thread is your recording of “Bora Scura,” which 10 musicians, including yourself, interpret in their own way. How did the project come about, and how did you choose the participants? What was important to you in the final product? The album also features the legendary Japanese musician KK Null, with whom you have collaborated before. How did you meet and start collaborating?

I must say that the album “Bora Scura Reimagined” was created back in 2019 but was released only last year; I tend to release albums at a slower pace. The first album from 2018 was well received, featured in media outlets like The Wire, and even ranked on various best albums of the year lists. The idea for reinterpreting the album came to me upon its release because the raw recordings of the storm are very intense and border on drone/noise. However, I somehow forgot about it or shelved it until Dejan Požegar (Neo-Cymex) reminded me with his rework. So I invited other artists to collaborate. The idea behind the “Bora Scura Reimagined” project was to manipulate and transform the raw, untreated storm recordings and present them in a different way, such as electronic mutations with each author’s imprint, ranging from more ambient versions by Max Corbach and Neo-Cymex to the violent noisy version by KK Null or Vomir, where the storm turns into a deadly tornado.

I have been in touch with all the participants on the album and have been following them for many years, so I already knew what interpretation I would get. I’ve been following Paul Schutze since the 90s; I used to listen to his albums “New Maps Of Hell” and “Site Anubis” frequently back then. I know KK Null from the days of the band Zeni Geva; he has also been a soloist here several times, and we collaborated on the “Signia” album and on Fabriksampler V4. Some artists chose a more conventional approach, using granular synthesis, filtering, morphing, while others went to extremes. Paul Schutze used spectral processing and algorithmic resynthesis, Daniel Menche played the recordings through a rotating Bluetooth speaker while simultaneously recording feedback with a field recorder. The reinterpretation album was also well-received; both albums were listed among the “40 Best winter albums of all time” on the A Closer Listen portal, which is interesting.

You are also a video artist. How does video differ and/or complement music?

Video and music should be equal; together, they form a powerful combination, creating synergy and an immersive experience. Since the 90s, I have been using video projections at concerts because I was alone on stage and wanted to liven up the performance with computer animations and digitally processed footage. I mostly shot material with a camera, then processed it with a computer. I often used software like Elastic Reality, which was popular at the time, for morphing and warping, synchronized with the music, and projected onto a screen. Synchronized video projections contribute to a sense of coherence between the visual and auditory elements. Both media complement each other in conveying messages; video helps to visualize the atmosphere and dynamics of the music, while music adds depth and substance to the video, which could otherwise remain disconnected from the viewer.

What is important to you in video? Do you approach these projects differently than musical ones?

It depends on the concept and the type of project. What matters to me is the ability to change and adapt the video in combination with the music to create the desired atmosphere by manipulating inserts in content and form. For short experimental films, I first tackle the video and then create the sound. I mostly work for screenings at various video festivals like Kino Otok, Festival Narave, Experiments in Cinema, Instants Video, Videomedeja… there have been quite a few of these festivals. For the audiovisual exhibition “Biodukt,” Martina and I recorded various forests from morning to evening, which was then played in the space on four walls. For video projections at concerts, it’s the other way around: first the music, then the video. I use a lot of fractal-generated video, processed footage of the Soča River for “Signia,” and abstract, processed video material for newer PureH performances, similar to CMBR. I have also created video projections for other bands, fashion shows, various TV commercials, and promotional videos for YouTube.

How important is the visual aspect for a musician and their music?

The visual aspect helps emphasize the message of the music itself, presenting concepts, creating a strong visual impression that remains in the memory of listeners. It contributes to the overall atmosphere with an additional atmosphere, whether it’s dark or abstract, psychedelic or meditative, thus influencing the holistic experience of the music. It can also create a recognizable image for the musician that listeners will associate with their music; for example, with the band Cadlag, the black-and-white aesthetic, analog TV noise, and VHS look have become part of the project’s identity and recognition.

What are you currently creating and preparing, and when can we expect something new?

Mostly, I work and create in the studio, mixing/mastering albums for other bands, from metal to electronic, as well as sound for various commercials, TV synchronizations, etc. I’m also involved in video production for external clients and producing various conceptual projects, audiovisual exhibitions, conducting workshops. As for my own projects, I’m currently in the phase of recording field recordings and various sonifications, microstructures, sound manipulations, sensors, applications. For example, a project that has taken a lot of my time is the Brainwave Sound System – a system for generating sound synchronized with brainwaves, presented years ago at the Slovenian Innovation Forum. The project has been in development for eight years, and I hope the final version will be ready soon. I’m also delving deeper into various AI tools and exploring them, especially machine learning for sound and video generation/synthesis. Martina and I are preparing some new projects, field recordings, and audiovisual exhibitions, and the storm will have a surround continuation. I have material for several Cadlag albums on disks; I need to finish and release them. I have a lot of new and old material for PureH and other factions as well… there are quite a few different projects, some of which have been on hold for quite some time, and I don’t know when something new will come out. Whenever it’s published.